Disputed Issues in Quechua

Contents

The Great Unholy Row: Three Vowel Letters or Five?

The Simple Proof to Show Which Alphabet is Right

Let’s Be Practical:

Which Alphabet is Going to Win Out?

But Aren’t There Five Vowels in ‘The Alphabet’?

including special

sections on:

Some More Notes on the Vowels Controversy, for Linguists

Other Disputed Issues

The Spelling of the City Name Cuzco (or Cusco, Qosqo, Qusqu…)

some of the articles previously on this page have been expanded and moved to this new, separate page on

Popular – and Damaging – Myths about Quechua

Did Quechua Come from the Incas?

Is Cuzco Quechua the ‘Proper’ Quechua?

Where did Quechua Come from Originally?

Cuzco?

The Identity of the ‘Secret Language of the Incas’

The Great Unholy Row: Three Vowel Letters or Five?

This question is so important that I’ve had to write something; I hope it helps! Much of this explanation is intended for anyone to read, indeed I’ve very deliberately tried to explain this issue in terms which will be clear for ‘Joe Public the non‑linguist’.

If you are a linguist, then you’ll know all this – it was probably lesson one in first your linguistics course – so you might want to skip straight to the technical stuff.

This page goes into the background to this whole debate, where things are going and who is on which side. It also explicitly illustrates all the problems that occur if you try to write Quechua with five vowels. On that last issue, you can now also find a fuller explanation of the reasons for spelling Quechua with only three vowel letters rather than five on a new website of mine, Sounds of the Andean Languages, and you may want to read that first.

For more information, if you read in Spanish, there’s another long article of mine on the

alphabets issue

Also, and ![]() , is this

article The View from Down

Under, (in

English and Spanish), by the Australian linguist Gavan Breen, giving his view

on the issue of which of the competing alphabets proposed for Quechua is best,

and why, from his experience of devising alphabets for aboriginal languages in

Australia.

, is this

article The View from Down

Under, (in

English and Spanish), by the Australian linguist Gavan Breen, giving his view

on the issue of which of the competing alphabets proposed for Quechua is best,

and why, from his experience of devising alphabets for aboriginal languages in

Australia.

The Short Story

Introduction

The alphabets issue is an absurdly bitter, divisive and counter‑productive one in Quechua in the Andean countries, and a huge amount of effort and often very uninformed arguing has been wasted on it, which would be much better put into producing more work in and promoting Quechua, even in the ‘wrong’ alphabet for now. In reality so long as people are bilingual in Spanish, which does include most Quechua‑speakers, they can viably use either alphabet in practice when it comes to it (though they might protest violently, they can still read either).

That, at least, is a commonly expressed and fairly sensible, practical view. However, the issue is very important not just on a theoretical but also on a very practical level too. This is because in the Andean countries the perception that Quechua has no agreed norm or standard for writing it is very widely taken as a sign that it’s not a ‘proper, written language’. This is linguistic nonsense, of course – Quechua like any language has just as much merit as Spanish, English or any other language any people speak. But the reality is that this perception is very powerful and dangerous, in that it only reinforces the downtrodden status of Quechua with respect to Spanish, and thus contributes to its possible long‑term extinction. So the sooner this issue ends, the better. It does matter, and it also matters to choose and support the right alphabet, as diplomatically as possible when necessary, as it often is, but do stick with the right one.

So, what are the competing alphabets? Well there are some important differences in usage of consonants, but the really big issue is how many vowel letters to use, three or five:

• Fans of the three‑vowel <a> <i> <u> alphabet (these people go by the name of ‘tri‑vocalistas’) are generally linguists, educationalists, governments and their education ministries, and most younger people, especially those who have learnt this alphabet in school over recent years. In this spelling system the letters <e> and <o> are not used to write native Quechua words, and are reserved only for Spanish loan-words whose pronunciation has not been adjusted to Quechua.

• Fans of the five‑vowel alphabet, i.e. <a> <i> <u> plus <e> and <o> (alias ‘penta‑vocalistas’), are generally not professional linguists, and are middle‑aged and older Quechua‑speakers who never had the chance to learn to write Quechua when they were at school, but are completely bilingual in spoken and – most importantly for this issue –written Spanish. These people were instrumental in the early years of the Quechua revival in the 1960s to 1980s, and continue to publish considerable amounts of work in Quechua. Indeed the (pretty much self‑appointed) Cuzco and Cochabamba branches of the Quechua Language Academy are full of pretty solidly five‑vowel fans. But they are not professional linguists.

Note that the Peruvian Ministry of Education itself initially (in 1975) went for an official alphabet with five vowel letters, but then revised this in 1985 and switched to the three‑vowel one. Whatever many people may say, the three‑vowel alphabet is the official one in Peru, and all government educational materials in Quechua are now produced in it. The three‑vowel alphabet is also the officially sanctioned one for education in Ecuador and Bolivia too.

The Simple Proof to Show Which Alphabet is Right

The crucial sentence above when I wrote above that either alphabet can viably be used in practice when it comes to it, the crucial rider to that was so long as people are bilingual in Spanish. For adults (mostly women) and particularly children who do not yet know Spanish well, however, it is very clear that one of the proposed alphabets is dead wrong.

This is because what it insists on is that in order to read and write their own native tongue correctly, Quechua‑speaking children must learn first of all how to pronounce pretty much perfectly a different language they does not necessarily know, and one that moreover has a pronunciation system completely alien to their native language, in this case Spanish.

Put yourself in their position: as a native speaker of English (or whatever your own language is), do you think you should have had to learn the perfect pronunciation of Russian when you were five years old, just in order to write your own language? If that isn’t both (a) discrimination, (b) unfair, and (c) plain stupid, I don’t know what is. No surprise then, that all educationalists working in teaching Quechua always use the other, linguistically correct alphabet.

It is a truism in the Andes, and a stigma Quechua‑speakers continue to suffer from terribly, that native Quechua‑speakers have difficulty in distinguishing the pronunciations of Spanish <e> from <i> and <o> from <u>. They just can’t do them, and say things like nu tingu instead of no tengo, or indeed mix them up by trying to hard (‘hypercorrection’), saying things like grengo for gringo. This Quechua accent in Spanish is known as motismo, from the various pronunciations of the originally Quechua word mut’i borrowed into Spanish as mote.

This is the whole point. If native Quechua‑speakers who aren’t very good at distinguishing the sounds Spanish users write <e> and <i>, and <o> and <u>, it’s precisely because that distinction is immaterial to them in their language. If they can’t even make the distinction between these sounds properly and know when to say which, how on earth will they be able to write them properly, and know when to write which? And what are we doing requiring this of them just in order to write their own language – just because it suits us because we do in our language, Spanish (or English, etc.)?

Five vowels is nothing but an alien imposition of Spanish on Quechua. I’ve sometimes been asked what the Incas would have written if they had invented their own writing system. One thing is clear in linguistics: no language has ever been written down by its native speakers using different symbols for sounds which are not used distinctively in that language. The Incas would have used three symbols for their vowels, not five.

Now you might say that there aren’t that many Quechua‑speakers who don’t already know Spanish, so that argument doesn’t matter too much. First point: doesn’t matter to whom? Yes, many of these bilingual speakers are resistant to the three‑vowel alphabet at first. With a little explanation and practice most very soon come to get it and make the switch. Yes, that is what they need to be asked to do – and it’s not me, a foreigner, asking them, it’s their own compatriots, linguists, education ministries, and many other Quechua speakers asking them to give it a try in the name of establishing a Quechua unity, because a three‑vowel alphabet is the only possible way to achieve that. And in any case there are plenty more good reasons.

Far more practical proof than what the Incas would have done is that writing with the five Spanish vowel letters simply doesn’t work for Quechua. The other rider to my comment about the viability of the two alphabets was that either can viably be used in practice. That only holds, though, so long as you don’t insist on everybody spelling the same word the same way, or indeed the same person spelling the same word the same way each time he or she writes it. If you’re prepared to tolerate such randomness in spelling, you can use five vowels.

Switching to three vowels has the huge advantage, however, of instantly defusing once and for all any arguments about Quechua’s vowels should be spelt. It also allows everyone to pronounce according to their local pronunciations, but still all spell words the same so they can read each other’s written Quechua no problem (just as we do in Spanish and English, one of the only good reasons for keeping the chaotic English spelling system as it is). There are plenty more details on this below, with lovely illustrations of the hopeless randomness in spelling with five vowels, even in dictionaries.

Let’s Be Practical: Which Alphabet is Going to Win Out?

Let’s be practical then: let’s bet on a winner. So which alphabet is the best bet, the one that will win out in the end? Well, other than the three‑vowel one being simply ‘right’, there are plenty of other purely practical reasons to back it. It has become increasingly clear even over the last five years that only one of these alphabets has a future: the three‑vowel one.

• It’s now the official alphabet in all three main Quechua‑speaking countries – Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador.

• It’s used by almost all educationalists in Quechua, and therefore all schoolbooks. Almost all children learning Quechua at school in the Andes are learning with three vowels. They will soon be becoming adults and some of them will join the ranks of people writing in Quechua.

• Proof that this is already happening: of the number of new books published every year, more and more are now in the three‑vowel alphabet, not the five‑vowel one which used to be the majority one a decade or so ago. (Even the new edition of the Lonely Planet phrasebook has switched!) New teaching materials are almost all in three vowels.

• Many individuals are themselves switching from five to three vowels. I myself was initially rather ambivalent and learnt with materials in five vowels. As I realised more and more how random and unsatisfactory that alphabet is, I have since changed and become convinced: I’d never use five vowels myself now. The most well‑known Quechua proponent in Bolivia, author of textbooks in five‑vowels, has bravely gone public that he too now favours three vowels.

• I’ve never met anyone who has ever switched using from three vowels to five. Once they see the problems with using five, they never go back.

• The most ardent diehard supporters of using five vowels are now almost all in their fifties, sixties or seventies.

• The five‑vowel writers never agree amongst themselves on how to write the same word, arguing over which words should be written with <i> and which with <e>, which with <u> and which with <o>. For some scanned examples, click here. Three‑vowel writers never argue amongst themselves about this! The only way to stop the arguments is to use three vowels. (The same goes for the similar problems in consonants, whose pronunciation varies from region to region).

But Aren’t There Five Vowels in ‘The Alphabet’?

But aren’t there five vowels in the alphabet? Hold on! There were in Latin, whose speakers invented the alphabet we’ve got. There aren’t in other alphabets, like Greek or Cyrillic (for Russian). In fact the fact that Latin only has five vowel letters makes it a real pain for writing languages that have more distinct vowel sounds than Latin did. Why do you think so many languages have to resort to accents and festoon their letters with signs like this: é, ü, ã, ø? Or write letters double met vs. meet, put vs. putt, or use two different vowels together bed vs. bead, or write extra letters later that you don’t pronounce hop vs. hope? Or just give up trying read vs. read (= reed vs. red)? Hence much of the huge mess English spelling has got into (my pronunciation doesn’t have five distinct vowels, it has bead, bid, bed, bared, bad, bard, bird, booed, bud and hood, not to mention combinations like bayed, bowed, bode, buoyed).

No, all of this has happened precisely because languages don’t always have the same sound system as was appropriate to how people spoke in Rome about 2000 years ago! In particular, they do not always have the same number of distinct vowels. Luckily for Spanish, by a very roundabout route it has come back to a stage where it has the same as Latin.

Quechua is different. It does have plenty of vowel sounds, and ones that to us sound pretty like the ones we’re used to writing with the letters <e> and <o>. But the sound system is completely different, and it is not appropriate to use those letters for Quechua words. Trust me on this!

What’s the Basic Problem?

The problem with the three‑vowel alphabet is not that it is wrong, for it isn’t. The ‘difficulty’ is that it is rather different from the Spanish spelling system. As it has to be, of course, for after all they’re different languages with extremely different vowel systems, so they need different spelling systems to reflect and respect that.

So the real problem is only one of understanding what alphabets are for and how they work. The majority of Andeans are used to reading and writing only in Spanish, and have a perception that how Spanish is written is somehow ‘how you write sounds’ in general, on some sort of universal level, valid for all languages. They generally have little experience of writing and pronouncing any other languages to come to the realisation in practice that actually each different language has its own spelling system, adapted and appropriate to the particular, distinct sound system of that language.

Some examples to illustrate the basic principle that the attractive idea of ‘spell as it sounds’ is actually simplistic and completely wrong. Letters and sounds do not always correspond one‑to‑one either between languages or indeed in any one language (you might not have noticed, or have ever listened hard enough to, but if they really did it would be impossibly difficult to read and write even your own language):

• the same letter <j> does not correspond to the same sound in English jet, French je, Spanish José and German ja

• while the second consonant in Spanish sed thirst and English path are written differently, they are actually often exactly the same sound

• while the two consonants in Spanish dedo finger are written with the same letter <d> in Spanish, they actually correspond to different sounds, the first like the one written <d> in English day, the second like the one written <th> in English mother.

So the basic solution in the case of Quechua? Use the three‑vowel alphabet, and for those people who already know how to speak and especially write Spanish, explain properly to them why the Quechua spelling follows different rules, and why it needs to.

The Full Details

The nightmare of this issue is not in the issue itself – like I say, most Quechua speakers can generally get by with either – but in how the decades of ridiculously acrimonious dispute about it have sapped so much energy of Quechua specialists that should have been put to much better and more practical use in promoting Quechua. In particular, there is an apparently unbridgeable gulf and indeed intense mistrust and dismissal of each other by linguists on the one side, and the old guard of the (self‑appointed) Quechua Language Academies in Cuzco and Cochabamba.

This is a tragedy when Quechua is in real danger and decline. I hope to do something about it, and I urge everyone not just to use the three‑vowel alphabet, but also to help spread a feeling of live and let live, and to try to get people to listen and reason, and work together for the good of Quechua. In particular, linguists should try to be as diplomatic, clear, and as unbelievably patient as possible when trying to explain why the three‑vowel alphabet is best. There are some very ingrained attitudes out there! If you’re not a linguist, just explain that you trust the official alphabet, you find it quite workable, and stick politely to it wherever you can.

The question of how many vowels to use to write a language may strike non‑linguists as obvious and pointless, but believe me, it isn’t by any means! Part of what infuriates people is that it’s connected with the issue of treating Quechua properly as a language in its own right, rather than one on which just to impose our own reflexes from using European languages. It’s not a simple matter, and non‑linguists are automatically completely confused by other languages they speak, especially in the case of all educated Quechua‑speakers, means Spanish (which of course uses 5 vowel letters…). If you’re not linguistically trained, you really will have to make a little effort to overcome your instincts from speaking Spanish or English, and suspend your disbelief, in order to understand this issue from a native Quechua point of view! Please!

Above all, throughout all of this, remember this: you’re coming at Quechua only after you’ve already learnt the English (and probably also the Spanish) sound systems, alphabets, spelling and pronunciation rules. Quechua is a different language, and as such deserves its own spelling system – and that includes its own rules for how to pronounce certain letters in the alphabet.

The big row is: should you use just the three vowel letters <a>, <i> and <u> for Quechua, or do we need to use <e> and <o> too? This is a nightmare problem, mostly because if you just listen to your native language (English, Spanish, etc.) reflexes, they’ll lead you astray. Even if you’re a native Quechua‑speaker, if you’re also fluent in Spanish – which even more importantly means you’ve always read and written with an alphabet designed for Spanish, not Quechua – your acquired Spanish reflexes will confuse you completely, and probably lead you to the wrong instinctive assumption, that Quechua too needs to be written with five vowels.

First, you must make sure you distinguish between actual sounds, which here will be written between square brackets [ ], as in [o], and letters, written here between < > signs, so <o>. It is crucial never to forget that written letters are nothing but symbols, they are obviously not sounds in themselves! Pronounce the words harmony, harmonic and harmonious, for instance, and you’ll see how the letter always written <o> in each is actually pronounced in three completely different ways, different in each word.

So in certain ways, yes of course, letters do ‘correspond to’ or better ‘represent’ given sounds, but actually not necessarily perfectly one‑to‑one, even in an ideal, totally consistent alphabet (if you don’t believe this, hold on before you jump to conclusions!) So try hard not to confuse what are actually two quite different concepts: sound and letter. As more evidence of this, think how the same letter can represent completely different sounds in different languages: think of <j> in English jet Spanish Juan, German ja and French je, for instance: four entirely different sounds.

If you’re getting confused or at any point think that what is written below is not right, then stop, forget the spelling and just say things out loud to yourself, and listen for any differences you can hear when you say the words out loud to yourself!

It is a very popular misconception that a ‘good alphabet’ writes the language ‘exactly as it is pronounced’, i.e. any two different sounds are always to be written with different letters. Put this way, this is actually a gross oversimplification, and in fact plain wrong, even for the best, most consistent alphabets in the world! The ideal alphabet is actually one that writes as different letters only those sounds that are meaningfully different in that language; but leaves minor sound differences that are automatic and insignificant in that language (i.e. ones that don’t make different words) written with the same letter.

If you trust me on this, then you can skip this paragraph. If you’re suspicious, or think this should be how alphabets are written, then I’ll have to ask you to suspend your disbelief a little and read this paragraph, and the rest of this text, with an open mind. And with the modesty to recognise that there are lots of people out there – linguists, and especially phoneticians – who spend their whole professional careers looking in to questions of phonetics and alphabets, and they do know what they are talking about in their field. So even if at first you reckon they’re mad scientists, and you know better because you speak a particular language, give them a chance to explain. Sometimes a linguist can actually know better than a native speaker how a language and its alphabet work, because he/she has analysed them properly. It’s a bit like a patient paralysed with a broken spinal cord, who might furiously insist “But doctor, are you mad? It’s my leg that won’t move, it’s my leg that’s injured, not my spine!” It’s the patient’s own leg, sure, but it’s the professional scientist who actually knows the real nature of the problem! With a little thought put into understanding these issues, all will eventually fall into place, and you’ll see how it is nowhere near as simple as it first appears, and how the language(s) you already knew ‘tricked’ you into misunderstanding others.

So, back to the main point: the ideal alphabet is one that writes different sounds as different letters only if the difference between those sounds is meaningful and significant in that language. That is, it’s ideal also only if it actually ignores minor sound differences which in that language are automatic and insignificant (i.e. ones that don’t make different words), and actually writes such insignificantly different sounds with the same letter.

Now this doesn’t stop the same sound difference that is insignificant in one language being significant in another language, of course – because all languages have different sound systems. In any language where a particular sound difference is significant, then in that language’s spelling system it should be shown by using different letters for those sounds. This is the whole point of having a separate spelling system for each language, it’s indispensable to have them because each language’s sound system is unique.

Since native monolingual speakers are so practiced in their own language, they acquire speech reflexes which become so fixed in their minds that they actually can’t even reliably perceive any more certain sound differences that are insignificant in their language. So it’s only the type of alphabet that doesn’t force them to listen out for such differences that will be natural and easy for them to use. Sound systems are actually far more complicated than even their native speakers realise, and the best alphabet is one that writes the language exactly as its native monolingual speakers conceive of and perceive its sounds.

Don’t underestimate the importance of these ‘reflexes’ you learn with your native language(s). Anyone who grows up right from birth in the environment of any particular language will pick up its sound system and pronunciation more or less perfectly, ‘natively’ . However, the more you practice this language, especially if you learn this one exclusively, the more you acquire its sound system as simple unconscious reflexes (this is what getting ‘native’ skills is all about), and ignore any sounds and sound differences that aren’t relevant to that language. So, while the exact age of course varies from person to person, generally by about age 7 you’re so practiced in your native tongue(s) that you will no longer necessarily ever be able to unlearn its sound system’s reflexes, and thus may never get a perfect accent in languages you learn after that age. Your native language reflexes make it much more difficult for you to pronounce, and even to hear, particular sound differences that your language doesn’t use at all, or just doesn’t use in the same way

So, all alphabets for all languages are based on the principle mentioned above: different sounds are written as different letters only if the difference between those sounds is meaningful and significant in that language. Minor sound differences that are automatic and insignificant in that language (i.e. ones that don’t make different words) are written with the same letter. Otherwise the alphabet would be pointlessly complicated and difficult for native speakers of that language.

The Spanish alphabet is in fact widely recognised as one of the ‘best’ in this regard, precisely because it follows these principles very closely. In no alphabet in the world, even ‘perfect’ ones, does one letter always necessarily correspond to only one sound. Spanish spelling is just like this too. The Spanish letter <d> is often pronounced [d], but sometimes – in certain specific, predictable circumstances – it automatically comes out naturally like the [th] sound in English ‘the’ (the main circumstances are when the <d> is surrounded by vowels, both before and after it). Compare the two different sounds in Spanish dedo (finger), both written with the same letter <d>.

Now English‑speakers, however, can hear these as clearly different sounds – a bit like if this word were written in English ‘deitho’ – but they can only because the difference between the [d] and [th] sounds is significant in English. The point is, it’s only their English that makes them aware of and attuned to this difference; native Spanish speakers with no English will not generally notice the difference.

You can prove that this sound difference is significant, meaningful, in English, because these are the only sounds that distinguish the words day and they, or other and udder (forget the irregular English spelling of the rest of the words, just listen to the sounds and you’ll hear that this is true!). No words in Spanish can be distinguished by these sounds alone.

And hey presto … unlike in Spanish, in English we do write these two different sounds with different letters, <d> and <th>, even though they’re the same two sounds that Spanish only uses one letter for, <d>. Why don’t the Spaniards write these with different letters, if in truth they are different sounds? Precisely because the difference is not significant in the Spanish sound system, which means that a Spanish‑speaker who doesn’t know English will be so used to the automatic reflexes of his language that he or she simply won’t hear this difference properly or be conscious of it. So for him or her it would be pointless to write the sounds differently, and very difficult to tell them apart reliably.

In fact there’s even more variation than this in Spanish, with a third possible pronunciation of Spanish <d>: word-finally in words like verdad (truth), it often comes out as a voiceless version of ‘th’, as in English think, not voiced as in the. Indeed this is actually the same sound represented by <z>, <ce>, or <ci> in Madrid Spanish, though not in South America. This separate, though related issue just goes to show quite how complex the sound systems of languages are when you look into them, and how the mantra of ‘one sound one letter’, at first sight so apparently straightforward and appealing, is actually hopelessly simplistic the moment you start really thinking about the sounds of a language.

This further distinction between these two types of <th>, voiced and voiceless, is also significant in English, if only marginally in occasional pairs like thy and thigh. Still, English speakers therefore hear it clearly, but Spanish-speakers do not. Ideally, in English spelling really it should be distinguished by different letters, as it was in old English and still is in modern Icelandic with its <ð> and <Þ>, but there are so few contrasting ‘minimal pairs’ of words like thy and thigh that we get away without it (the inconsistent spellings of the ends of these words helps us out!).

Anyway, to get back to Quechua, just as it is quite pointless (and indeed difficult) for Spanish-speakers to spell the various different pronunciations of their <d> differently, even if a knowledge of English makes you feel like you should, so likewise, a knowledge of Spanish, in which the difference between the sounds [u] and [o] is significant, will give you the wrong reflexes and assumptions for Quechua, where this sound difference is not significant, and so should not be represented in Quechua spelling.

Just like it’s only his or her English reflexes that make an English‑speaker aware of the [d] vs. [th] contrast insignificant in Spanish, so it’s only that fact that they also know Spanish that makes bilingual Quechua speakers aware of and attuned to the difference between the sounds [u] and [o], insignificant in Quechua. So if you insist on representing this insignificant difference in the spelling of Quechua (by writing with five vowel letters including <o>), what you are actually doing will:

•

make

the alphabet pointlessly difficult for monolingual native Quechua‑speakers

to learn

•

misrepresent

the sound system of the language, pretending it’s like Spanish

•

come up

against endless problems of natural variation in the language in the exact

pronunciations of sounds which aren’t significant in that language.

So, all alphabets do in fact have different sounds which are represented by the same letter, wherever the choice between those sounds is automatically made by the sound rules of the language in question, and the sound difference can’t be used to make a difference in meaning. The point is, your language’s alphabet was specifically designed to make it easier for you, because if you’re a native speaker, you’re so used to these automatic rules that you don’t even hear the sounds as different any more. These reflexes are one of the big reasons why one always has trouble getting rid of one’s accent in a foreign language!

What all this means for Quechua is that the best alphabet for monolingual Quechua‑speakers is clearly the three‑vowel one – which is precisely why this is the official one used in education in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador. For them, it is automatic and easy to learn (any difficulties come not from it being inappropriate for Quechua, but from confusion with the Spanish system that they are also taught around the same time).

For you, if you speak another language that does make a significant difference between [u] and [o] sounds, and so uses an alphabet that does have different letters for them (<u> and <o>), part of your learning Quechua will be to learn how its sound system works differently to that of your native language or others you know. This means too that in learning the Quechua alphabet, you have to learn in what circumstances – basically, anywhere near the letter <q> – you have to automatically pronounce the letter <u> with a sound rather more like the one you’re used to writing ‘o’ in your alphabet. For an illustration, see the above notes on the Quechua spelling of Qosqo vs. Qusqu. Remember, whichever alphabet is used, the pronunciation is the same: more or less [qosqo]. The alphabet is to represent the pronunciation (according to a set of rules), not dictate it!

In Quechua, exactly the same holds for the opposition between the sounds [i] and [e]. Both are written as <i>, [i] is the basic pronunciation, with the sound [e] used only near the letter <q> (or <h> derived from it).

Counter‑Evidence?

Many Quechua‑speakers who know Spanish will try to tell you that the difference between the sounds [i] and [e] in Quechua is significant, because either:

• They can hear it. Well of course they can hear it, now that they can speak Spanish, which has forced and trained them to be aware of this sound difference since it’s essential in Spanish. The point is not whether people bilingual in other languages can hear the distinction clearly, it’s whether native speakers of Quechua (and Quechua alone) can or not – it’s that which determines the spelling system appropriate for that language.

• Some of them claim that there are pairs of Quechua words that differ only in these sounds (though other five‑vowel fans also insist that there aren’t). In almost all the word‑pairs they propose to prove this, however, they forget to notice that there is another difference, between the sounds <k> and <q> (again, its their practice with Spanish and its alphabet which has no Quechua distinction of <k/c> vs. <q>, that leads them to overlook this). It’s only this difference between the consonants that is actually significant in Quechua, and it alone is quite enough to distinguish the words (as it distinguishes, for instance, kan there is from qan you). Indeed it’s the very presence of a <q> that forces the different vowel sound [e] or [o], instead of the [i] or [u] in the word with <k>. If they come up with other examples, please let me know (there are a few proposed cases, but none is convincing and there is always another more plausible explanation).

Advantages of the

Five‑Vowel Alphabet?

Despite all these ‘theoretical’ advantages of the 3‑vowel alphabet, and the huge practical advantage it has in being best for monolingual Quechua‑speakers to learn at school, one has to recognise that there are some practical reasons which might argue for a 5‑vowel alphabet.

The first is that, like it or not, many of the professional people who work with Quechua have already learnt, and long been using, the 5‑vowel alphabet, and insist on using it (almost always without understanding the issues, it must be said). The result is that there are quite a lot of texts already published in this alphabet, perhaps still just the majority.

The reason they prefer the 5‑vowel alphabet is simple: these people are generally in middle age, and went through school and all their professional university education entirely in Spanish, at a time when Quechua was very little written at all, and certainly not taught in schools. So all these people are much more practiced in, and at home with, written Spanish than with written Quechua. So they naturally prefer for Quechua an alphabet that most closely follows the rules they have already learnt for Spanish, and which indeed they feel as more natural after decades of using them. Obviously they prefer not to have to learn new rules appropriate for Quechua, and want to still use the same ones they’re used to, not realising that they’re only Spanish rules, not some ‘universal’ uniquely correct ones. They fail to see that as a completely different language with a completely different sound system to that of Spanish, Quechua should have its own alphabet and spelling and pronunciation rules. Their attitude is based in a complete misconception of how alphabets work. Not that they realise it, but it’s only because they are bilingual in Spanish that they hear the sound differences that are not significant in Quechua, which monolingual Quechua speakers do not hear distinctly. And they insist that “different sounds have to be written with different letters”, without understanding that this is actually wrong, and not what they do themselves in writing Spanish!

There is arguably one other reason for using five vowel letters. This is that it is easier for foreign learners of Quechua, because they can see immediately in the spelling when to pronounce [u], and when [o], without having to remember the rule that tells them when to. This is why many Quechua books for foreign learners use the 5‑vowel alphabet. This is hardly a good reason though. The rule is actually very simple and easy, and in any case, it is part of Quechua! It’s just like many other rules that you have to pick up as a foreign learner of any language, if you want to speak it and read its alphabet. Just like in learning Spanish pronunciation you have to learn the rule of when to pronounce the letter <d> as [d], and when as [th], and so on. Nobody is about to suggest that Spanish should change its spelling system to help make it easier for English speakers! A language’s alphabet is intended to be appropriate for that language’s sound system, and easiest for its native (especially monolingual) speakers. It is not designed to make it easy for foreigners of a particular other native language! Learning a language’s own sound and spelling systems is simply a normal part of learning that language. Foreign learners should hardly be in a position to dictate to native speakers how to write their language in what for them are unnecessarily complicated ways, just so that it’s easier for the foreigners to learn! Foreign learners who think they can dictate like this should show some respect for the language they’re trying to learn and its speakers!

Five Vowels Means Spelling Chaos

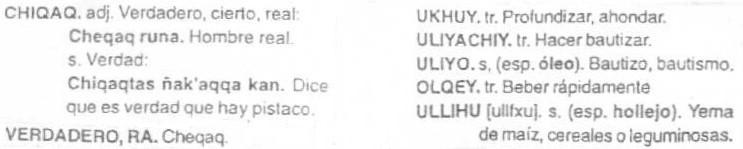

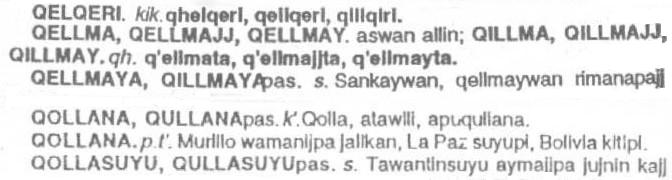

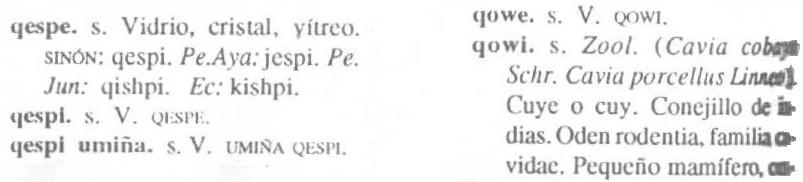

In any case, one point is clear in practice. Those who want to write with five vowels end up never being able to decide when to use which. Precisely because in Quechua the variation between these sounds like [i] or [e], or [u] or [o], can vary considerably in the precise pronunciation, even for the same speaker. Proof? There is ample… Here are some images scanned from some five-vowel dictionaries, just to show you the variation, randomness and chaos in spelling that are inevitable if – like the authors of these three dictionaries – you go for five vowels. In a three vowel spelling, this problem simply disappears… Note in the first one the variation in spelling of the same word <chiqaq> and <cheqaq>, and how the entry <olqey>, is lost in the middle of the words beginning with u- ! Similar problems occur in the other two dictionaries too. (The text is an excerpt from a different article of mine in Spanish on this issue).

Antonio Cusihuamán’s Cuzco-Collao Quechua dictionary

click here to see

full bibliographical details

in the Quechua-Spanish section is <chiqaq> (true) as the main entry,

but in the examples that follow it, we see the first as <cheqaq runa>, but another the second as <chiqaqtas…>

In the Spanish‑Quechua section, meanwhile,

for the entry verdadero (true) we get rather <cheqaq>

And in the Quechua‑Spanish section, lost

among the entries in alphabetical order under the letter <u>

one finds the entry spelt <olqey>, sic., starting with <o>!

The dictionary by Angel Herbas Sandóval, a member of the

Cochabamba Quechua Academy

click

here to see full bibliographical details

one finds <qelqeri>, but ‘alternatively, the same’ [kik.] <qellqeri>

y <qillqiri>

one finds <qellma>, and in this case ‘better’ [aswan allin] <qillma>

one finds <qellmaya> and in this case ‘also’ [-pas] <qillmaya>

The same goes for <qollana> and <qullana>, <qollasuyu> and <qullasuyu>

As you can see, the author sometimes prefers or

considers better the form with <i>, sometimes with <e>, and sometimes he doesn’t mind which.

The Cuzco Quechua Academy’s Dictionary

click

here to see full bibliographical details

<qespe> is given as

the main entry, but also <qespi>

Only the compound <qespi umiña> is given however, and not <qespe umiña>

<qowe> is

given, but also <qowi>

Those shown here are just a very few examples of all those to be found. This randomness, hesitation and inconsistency exists for a great many of the words in these dictionaries that contain a <q>. In all works by writers who use five‑vowel spelling – texts, grammars and dictionaries – one always finds such inconsistencies in spelling.

For your information, and as an illustration of the (flawed) logic of the proponents of the 5‑vowel alphabet, here is a link to an article (in Spanish) in favour of the 5‑vowel alphabet. The whole point is that the author has completely misunderstood the basic principle of how alphabets are designed (technically, they are phonemic, not absolutely phonetic). His opening paragraph makes this clear, in that he falls into the classic oversimplification trap of the claim that “every different sound must have a different letter”. He fails to consider the concept of whether sound differences are or are not significant in any particular language. As no phonetician, he can’t hear all the other actually quite different sounds that even with his alphabet he writes with the same letter. His proposed alphabet is simply a combination of those sound differences that are significant in Quechua plus those that are significant in Spanish (even if they aren’t in Quechua!).

Because he can’t analyse the influence his Spanish has on his ability to perceive certain sound differences, quite the opposite of what he claims, it is actually his alphabet that actually misrepresents the Quechua sound system by adding bits of the Spanish sound system to it.

At the very best, one might say for this alphabet that it might arguably be easier for Quechua‑speakers who are entirely bilingual in Spanish. And of course that means a hefty proportion of Quechua‑speakers. It’s still not a very good basis on which to design an alphabet for Quechua though.

Yet however unfortunate and open to criticism their reasons for preferring a 5‑vowel alphabet may be, the fact remains: in practice there are a whole lot of people out there who can make an enormous contribution to Quechua, and who insist on the 5‑vowel alphabet. However unhappy in theory, this remains a serious practical argument in favour, at least for the moment.

Which Alphabet is

Winning?

Still, in practice, which alphabet is more useful? I would suggest that it’s whichever one that has time on its side, whichever one is winning the debate, and increasing in use. Which is it?

It is true that many books published in Quechua do use the 5‑vowel alphabet. However, of more recent production in Quechua, especially with the expansion of Quechua‑teaching in schools, it is the 3‑vowel alphabet that is increasingly dominant in all three main Quechua‑speaking countries (Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru). This is particularly true in Peru since the change of the official alphabet to the 3‑vowel one in the 1980s. Moreover, with every year that passes, considerable numbers of children, and indeed their teachers, are learning the 3‑vowel alphabet only. It seems certain that it is this one that will win out in the end.

The best solution for everyone, and for Quechua, would be to get the two sides to work together.

Certainly, the 5‑vowel academicians need the help and advice of linguists, to improve the quality of their work. For despite their great efforts and admirable aims, their work is all too often sadly lacking because of their confusion not only on this issue, but on any question of grammar, pronunciation, lexicography, history, dialect varieties and sociology of the language, and so on.

Why are they so uninformed? Well, in large part precisely because the bitterness of the debate means that they often utterly reject any ‘linguistics’ as meaningless technical nonsense. Linguists are often little better in simply dismissing these ‘amateurs’ out of hand.

But like I said, both groups need each other, and Quechua needs them to work together. Linguists still need the 5‑vowel academicians too, because they are the best stock of educated speakers of careful, rich Quechua that we have, with perfect native instincts and big native vocabularies that most linguists, not native Quechua speakers, can never really aspire to. And anyway, they still have considerable clout in the real world.

So all in all there needs to be a lot more diplomacy, tact, respect and tolerance – all round.

Some More Notes on the Vowels Controversy, for

Linguists

As any linguist will have gathered from the above, the [i] vs. [e] and [u] vs. [o] oppositions in Quechua are merely allophonic, within the phonemes /i/ and /u/ respectively. It is true that the occasional linguist, most notably Cusihuamán (1976a) in his grammar of Cuzco‑Collao Quechua, has claimed the [i] vs. [e] and [u] vs. [o] distinctions have become phonemic in certain dialects of Quechua.

This is rejected by the great majority of linguists, however. Indeed, Cusihuamán himself was rather tentative in his claims, and there is a plausible explanation for the position he adopted. His book was sponsored and published by the Peruvian Ministry of Education, which at the time had (under the influence of the non‑professional, non‑linguists of the Cuzco Quechua Academy) initially published an official alphabet using the five vowels. Cusihuamán doubtless felt under pressure to toe the official line, since they were his publishers!

A few years later, however, on the overwhelming advice of professional linguists, the official alphabet was revised, and since 1983 it is the three‑vowel alphabet that is official (a fact the Cuzco Quechua Academy omit ever to mention!).

Certainly, there is a huge amount of variation in the actual phonetic realisations of the /i/ and /u/ phonemes in Cuzco‑Bolivian Quechua, both by region and by speaker. This of course only serves to reconfirm the allophonic, rather than phonemic, status of such variation.

And of course the effect on how people spell words with such variant phonetic realisations is entirely predictable. All writers who use the 5-vowel alphabet end up being entirely inconsistent in spelling the same words sometimes with <i>, other times with <e>; sometimes with <u>, other times with <o>. For a devastating account of this orthographic anarchy, see Cerrón‑Palomino (1992).

Can you therefore have recourse to a dictionary to check the ‘right’ spelling? Well a glance at the dictionaries published by the 5‑vowel advocates themselves serves only to reinforce this conclusion. They too are all over the place, and enter quite unfeasible amounts of ‘alternative’ spellings and pronunciations with <i> and <e>, or <u> and <o>. This is true of both Angel Herbas Sandoval’s Bolivian Quechua dictionary, and the Cuzco Quechua Academy’s dictionary, as Cerrón‑Palomino’s excoriating review of the latter makes only too clear.

Here are some examples:

Indeed, even experienced native-speaker linguists such as Antonio Cusihuamán, when forced to use the 5-vowel alphabet (because he was writing his grammar and dictionary for the Peruvian Education Ministry, at a time when their official alphabet said 5, so he presumably had no choice), are guilty of the same inconsistencies. Cusihuamán (1976b), now re-printed as Cusihuamán (2001b), has, hidden deep amongst all the words starting with <u->, the entry olqey (sic, on page 114)! Even for the same word, his multiple examples are inconsistent: for instance the entry for chiqaq/cheqaq and for its Spanish equivalent verdad (pages 32 and 209). There is similar inconsistency even when a phonetic transcription is given, as with yachachiq (page 16). There are also inconsistencies between his dictionary entries and the examples in his grammar: runtu vs. rontoqa, for instance. Lonely Planet’s hopeless old Quechua phrasebook had similar errors (e.g. both wawqe and wawqi), but thankfully it’s now being replaced by an infinitely better second edition, by a new author and using the 3-vowel alphabet.

Perhaps the biggest single argument in favour of the 3-vowel

alphabet is that it does away with all of this vacillation and orthographic

anarchy, inevitable when you try to make speakers represent purely allophonic

variation. It is also, of course, the

only viable alphabet for other varieties of Quechua which don’t have the

allophonic lowering at all, so much better as a standard pan-Quechua alphabet.

The general, natural rule about the uvulars /q/, /q’/ and aspirated /qh/ forcing the lowering of the /i/ and /u/ phonemes to something more akin to [e] and [o], or more open versions still, is pretty widely valid. However, there are considerable regional and ideolectal differences in the degree of such assimilation, depending especially on such factors as whether the uvular precedes or follows the vowel, and whether (and which) other consonants intervene between this uvular and the vowel, e.g. /n/, /r/, /l/, /s/, and so on. Cusihuamán himself points these out in considerable detail.

Indeed, in some cases one can hear lowering even when there is no uvular to condition it, with other sounds including /n/ and /r/ being claimed to condition lowering too, in certain circumstances for certain speakers.

Still, the bottom line is that, even if the precise distribution is not perfectly analysed yet and shows great variation, I have never found or been shown any convincing minimal pair that might establish more than three vowel phonemes.

A classic examples you may hear cited is the supposed pronunciation mot’e, which simply harks back to the hispanicised form mote. And in any case, the same Cuzco Quechua Academicians who will insist that that is the pronunciation actually also register the ‘variant’ mut’i in their own dictionary!

Another nice case is michi (cat) + genitive –q ® michiq, (cat’s) as ‘opposed’ to michi‑ (graze, herd animals) + ‘agentive’ suffix –q ® michiq shepherd (‘one who makes animals graze’). Ask the Academicians to pronounce them and you’ll get chaos!

However, if you are a linguist I implore you to take it easy and diplomatically on this issue! Please read my suggestions on how to solve the problem, and do what you can to help!

The Name ‘Quechua’

Coming soon! For details for now, see the section on this at the start of:

Cerrón-Palomino,

Rodolfo (1994) Lingüística Quechua

The Spelling of the City Name Cuzco

(or Cusco, Qosqo, Qusqu…)

More details coming soon! For now, see:

Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo

(1997) Cuzco

y no Cusco ni menos Qosqo

in:

Historica vol.21, pp. 166-170

The author of the above article basically recommends that in Spanish you should stick to the original and traditional spelling Cuzco, in which the z was never supposed to represent the Spanish ‘th’ sound, which didn’t exist at the time the name was first written. The z was used then to represent a pronunciation in Quechua distinct from the one they wrote with s. Since the time when it was first written thus, Cuzco Quechua has lost this sound distinction and both the original sounds are pronounced as s. The other, main grounds for changing the traditional spelling to Cusco were pretty damned silly, by the way. See the article. And even those who say you should use Qosqo in Spanish too are not proposing any adjective qosqeño instead of cuzqueño!

For writing in Quechua, the author recommends the three‑vowel (phonemic) alphabet, thus the spelling Qusqu rather than the Spanish‑influenced five‑vowel alphabet form, Qosqo. Whichever spelling system is used, it is absolutely essential to realise that nobody (especially not the linguists proposing the 3‑vowel spelling Qusqu) is suggesting that the correct pronunciation is anything other than with phonetic [o] sounds. Their point is, you shouldn’t read Quechua as if it were Spanish, since the two languages have completely different sound systems, and their alphabets are to be read as appropriate to the native sound system of each language. In Quechua, the letter <u> can be pronounced as either [u] generally, or [o] in certain specific cases, especially near the sound [q].

This may all strike non‑linguists as pointless, and for one word, who really cares, yes. All the same, the wider point about the vowels is a very important one, and if you want to treat Quechua properly as a language in its own right, not one that we just impose your own reflexes from using European languages, you have to make a little effort to understand this point! Read the section on alphabets above!